EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. It shows core operating earnings and helps readers gauge cash flow potential for a business or company.

Lenders, buyers, and investors often use this metric for a quick read on operating profitability. That said, strong EBITDA can coexist with low net income when taxes, interest, or depreciation cut into bottom-line earnings.

A good EBITDA looks like it is industry-specific, but benchmarks offer useful context. For example, as of 2025, the average EBITDA margin for service providers in the U.S. is around 9.8%.

EBITDA serves as a simplified metric that highlights operating performance independent of capital choices. In plain terms, it stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Each exclusion clears away items that can mask core profit.

The term removes interest and interest taxes because financing and jurisdictional tax rules vary widely across companies. It also adds back depreciation and amortization since those are noncash accounting charges tied to past investments.

This metric gauges operating performance before financing and accounting allocations. It gives a clearer signal of recurring earnings power and a near-term view of available cash.

Taxes and interest depend on jurisdiction and capital mix. Stripping them makes results more comparable across different markets and financing choices.

Caveat: this metric is not identical to operating cash flow and should be paired with other company financial measures when making decisions.

.webp)

There are two standard paths to compute EBITDA, chosen based on what the published reports show.

Start with net income and add back income tax, interest expense, and depreciation plus amortization. This path helps when only a consolidated bottom line is available.

Begin with operating profit and add depreciation and amortization. This is often cleaner when operating income is clearly stated on the income statement.

Example: net income $200k + tax $40k + interest $30k + D&A $50k = EBITDA $320k.

Watch errors such as adding non-debt interest, including sales or payroll taxes, double-counting D&A, or mismatching periods. Keep a one‑page reconciliation from net income to EBITDA for consistency and to support diligence. Since this is non‑GAAP, document the method used when sharing numbers with bankers or buyers like Elite Exit Advisors.

Benchmarks for operating earnings differ widely by market, so a single threshold rarely fits every firm. Use sector norms, company size, and growth profile to set realistic expectations rather than rely on one number.

Industry economics shape margins and capital needs. Asset‑heavy sectors often report lower operating ratios than software or services firms.

Smaller or early‑stage companies may accept lower margins while pursuing growth. Mature firms usually face pressure to show steadier earnings and higher margins.

As a rough rule of thumb, analysts often treat an operating multiple under 10 as above average for valuation comparisons. That guideline helps when comparing peers but does not replace cash flow analysis or capex forecasting.

Combine absolute operating earnings with margin and trend data to avoid misleading conclusions about true profitability.

Debt service capacity matters. Lenders and investors frequently assess earnings relative to interest to test resilience.

Bottom line: use a blend of absolute earnings, margin, and debt coverage to judge financial health. Elite Exit Advisors can help interpret these metrics within your industry and growth context.

EBITDA margin ratios reveal how much operating earnings a firm keeps from each dollar of sales. Use this metric to compare firms of different sizes because it expresses operating earnings relative to revenue.

The ebitda margin equals EBITDA ÷ revenue. It shows operating earnings before financing, taxes, and noncash charges as a share of sales.

A higher margin often signals stronger pricing power, tighter cost control, and a scalable operating model. Such firms tend to deliver better profitability and absorb growth costs more easily.

A lower margin may reveal higher operating overhead, weaker gross economics, or inefficiencies in production, fulfillment, or go-to-market. It can point to rising costs or thin pricing.

Example: $50M EBITDA on $100M revenue gives a 50% ebitda margin. That level suggests strong underlying profitability and margin leverage on added sales.

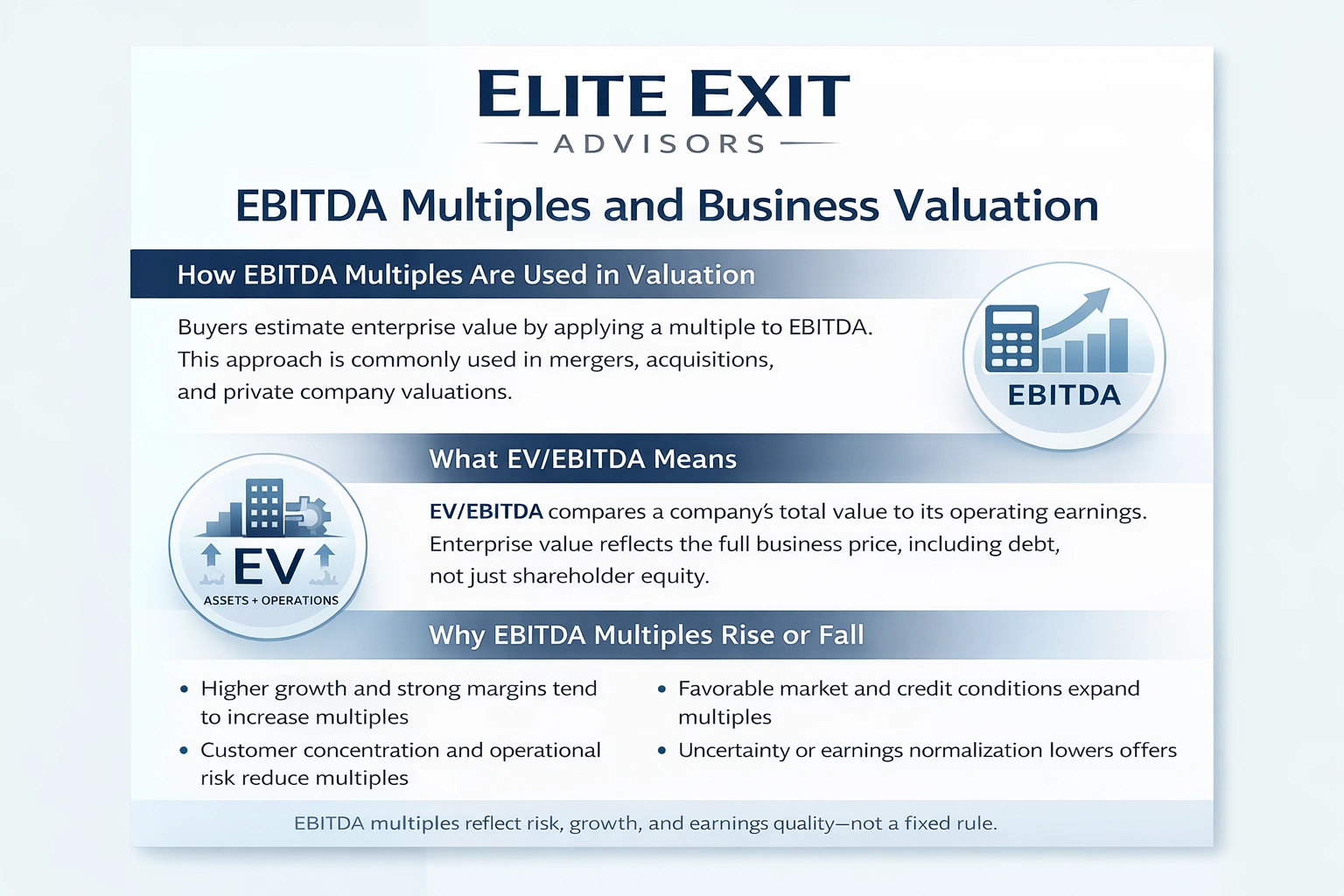

Many buyers turn operating earnings into price offers when they apply a multiple to those results. This method gives a fast estimate of enterprise value and is common in M&A and private company valuations.

Apply the chosen multiple to run‑rate operating profit to get enterprise value. Buyers then subtract net debt to calculate equity value for sale talks.

EV/EBITDA pairs enterprise value with operating earnings. Enterprise value represents the whole business price, not just shareholder claims.

Buyers usually revisit offers after diligence if earnings need normalization. Treat any multiple as the outcome of a clear valuation story backed by clean numbers.

Comparing ebitda with other income measures helps reveal where earnings come from and which costs matter most. Each metric strips different items from revenue, so choose the right one for your decision.

Net income reflects bottom‑line profit after interest, taxes, and noncash charges. ebitda removes those items. That makes the two figures diverge even when sales stay flat.

Gross profit equals revenue minus cost goods sold. It shows product or service economics before operating expenses. Use gross profit to judge pricing and production efficiency.

Operating profit follows gross profit less operating expenses. Depending on statement presentation, depreciation and amortization may sit above or below this line.

When to use each: gross profit for pricing and COGS control; operating profit for cost discipline; net income for bottom‑line health; ebitda for cross‑company operating comparisons. Beware relying on one metric, capital‑intensive firms may hide real asset consumption behind noncash addbacks.

Triangulate multiple measures when evaluating performance. Elite Exit Advisors can help interpret these metrics for valuation and negotiation.

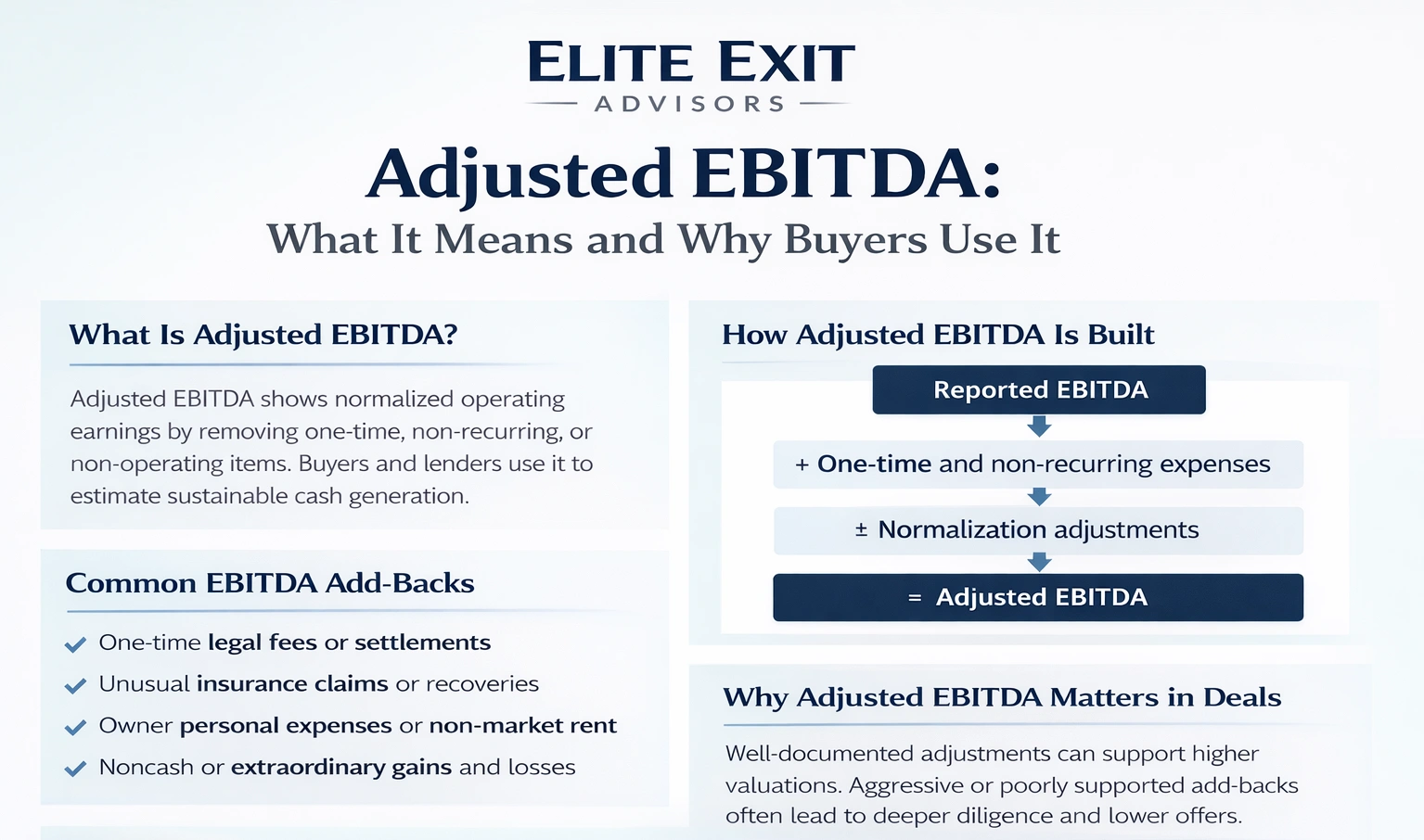

Adjusted EBITDA normalizes operating earnings, as it removes items that don’t reflect recurring core performance. Buyers and lenders rely on this adjusted view to estimate sustainable cash generation and to underwrite valuation and deal terms.

This measure starts with reported ebitda and adds back one-time, nonrecurring, or extraordinary items that distort ongoing results. The goal: show repeatable operating performance the next owner can expect.

Credible adjustments can raise reported earnings and support higher valuation multiples. Aggressive or poorly documented add-backs often trigger deeper diligence and push buyers to cut offers.

Documentation matters: invoices, contracts, and clear rationale help defend each adjustment during due diligence.

Remember: adjusted results still aren’t cash. Pair them with working capital and capex analysis. If adjusted figures look dramatically better than reported numbers, expect tougher questions on quality of earnings.

Lenders and acquirers treat reported operating results as a starting point for deeper review. That figure gives a quick sense of recurring earnings power across similar businesses and helps rank investment targets.

Bankers use the metric to estimate cash available to service long‑term debt. Underwriting often converts operating profit into coverage ratios that guard lenders against default.

Common covenant tests tie earnings to interest and scheduled principal. If coverage slips, the company may face restrictions on dividends, new debt, or capital spending.

Buyers typically anchor initial valuation to run‑rate operating earnings and apply a chosen multiple to get enterprise value. Then due diligence validates revenue quality, customer concentration, and margin consistency.

Discovery of unstable cash patterns or one‑off expenses leads to adjusted figures and revised offers. That process can change deal structure through earnouts, holdbacks, or different financing terms.

Takeaway for business owners: keep clear records and a defensible reconciliation. Clean reporting speeds approvals and reduces surprises in valuation talks.

Relying on a single operating headline can mask real cash needs and long‑term cost pressures. Readings that ignore spending and timing may overstate profitability for many firms.

When a company must invest heavily in equipment, facilities, or tech, that spending does not show up in the operating figure. Over time, replacement and upgrades create real cash outflows that depreciation and amortization only partly reflect.

Companies often calculate this metric differently. Regulators expect reconciling that number back to net income and full disclosure of add‑backs and taxes to protect users from inconsistent reporting.

The headline number ignores receivables, payables, and inventory swings. Those items can turn profitable accounting results into negative cash in the bank.

Practical checklist: don’t use this metric alone when:

A clear bridge linking volume, price, and cost drivers helps managers steer margin and valuation. Focus on steady moves that lift revenue and trim waste without harming customer value. The average EBITDA margin across all industries is approximately 32.2%, though this varies widely by sector, from under 10% in reinsurance to over 60% in green energy and tobacco.

Use pricing optimization, better sales mix, and retention programs to grow recurring revenue while defending contribution. Expand distribution where margins hold. Each action should target higher unit economics, not just top-line growth.

Negotiate supplier terms, cut waste, improve labor scheduling, and stop low‑ROI spend. Review cost of goods sold for sourcing and yield improvements. Small cuts multiply when repeated across spend lines.

Standardize processes, shorten cycle times, and improve forecasting to reduce stockouts and expedite fees. Better predictability lowers operating friction and preserves margin over time.

Refinance high‑rate debt, pay down leverage, or match term structure to cash generation. Lower interest costs raise reported earnings and free cash for growth. Align capital moves with long‑term company profitability.

.webp)

Buyers often adjust offers after diligence; proactive documentation limits surprises and preserves price. Elite Exit Advisors partners with owners to clarify earnings, prepare defensible reconciliations, and strengthen the valuation story before buyers arrive.

Interpret financials so you see which items drive recurring earnings and which will draw buyer scrutiny.

Standardize calculations and build a single reconciliation from net income that holds up under review.

If you want a clearer view of what your earnings really say about value, and how to improve that view, book a call. Our process focuses on readiness, documentation, and practical actions that lift both margin and credibility.

A clear assessment blends run‑rate earnings, margin strength, and evidence of recurring cash generation.

In practice, what counts as solid operating performance depends on industry norms, company scale, growth stage, and capital intensity. Use both the absolute ebitda level and the relative margin to see the full picture.

Remember that ebitda often drives valuation through multiples, but market shifts, risk, and growth expectations change those multiples fast. Accuracy matters: reconcile figures to net income, document adjustments, and avoid common calculation errors.

Finally, treat this metric as one lens among many. It can sharpen the operating picture, yet it does not replace cash flow analysis or a full check of financial health when judging business value.